Undersea cables are under threat, and they are the veins of our digital world

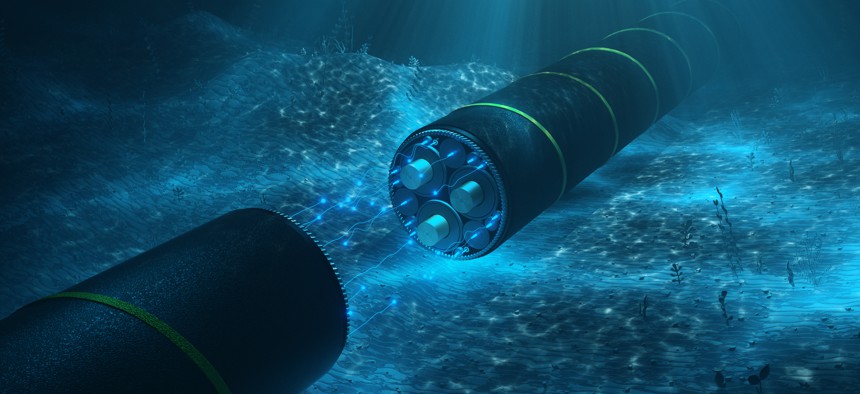

A model of an undersea cable that is laid along the seabed to transmit electricity and communications traffic. Gettyimages.com/ Serg Myshkovsky

As maritime sabotage rises, satellites hold the key to protecting them and ensuring global connectivity.

On Christmas Day, an undersea power cable in the Baltic and several telecommunications cables were severed. Western officials suspected sabotage: indeed, they have long surmised that Russia has been trying to cut through cables, but have thus far struggled to substantiate it.

But Finnish officials said soon after this event that miles and miles of tracks on the seabed pointed to Russian involvement. They believed that an aging Russian tanker had been dragging its anchor for ‘dozens of kilometres’, slicing through a cluster of valuable cables.

Whatever the truth, the rise in the number of subsea cable incidents puts internet connectivity at risk. And if cables are seen as legitimate infrastructure targets, then rising geopolitical tension will mean yet more sabotage is to come.

It’s worth noting how important subsea cables are. There are more than 500 of them worldwide, and they carry around 99% of all global internet traffic. They traverse some 300,000 kilometers of seabed, and more are being laid all the time. That’s to say that even though few of us even know of their existence, billions of us rely on them.

They therefore constitute fundamental global infrastructure: the means by which reliable connectivity, enabling many of the things we take for granted in modern life, is guaranteed across the globe. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a bipartisan, nonprofit policy research organization and think tank calls them the ‘soft underbelly of the global economy’.

Advances in satellite communications, including the proliferation of space sensor types, bring capabilities not previously available. One is the ability to track maritime traffic around the globe, and so in and around undersea cables, at a level of detail and at a speed not possible before. If a ship, or another entity, is acting in a way that could damage undersea cables, accidentally or on purpose, satellites can pick up on it. They can inform the relevant parties and enable them to take action to prevent any damage from taking place.

Accurate tracking requires the rapid transmission of data from satellites to the ground. And the problem here is that there are data transmission bottlenecks. Specifically traditional radio-frequency (R.F.) downlink systems are limited to Mbps speeds that struggle to keep up with the Gigabits of data generated every second from the myriad of satellites collecting data from space.

There is a need for low latency – for minimal ‘lag’ – in maritime monitoring that can be significantly improved with the advent of Gbps Optical Ground Stations. This points to the vital supporting role that optical communications has to play.

Optical communications systems, involved in transmitting data via laser from satellites to optical ground stations and vice versa, have significantly higher bandwidth, and can meet the growing need for fast, high-capacity information transfer. Already, these systems are capable of transmitting data at Gigabit speeds with a path to Terabit speeds.

But satellites with optical links can do more. Because of the significant increase in downlink speeds, not only can they support the tracking of ships and other maritime vessels, but with Gbps data transmission speeds, optical ground links can provide an impactful alternative path and resilience to the undersea cable network of internet connectivity.

Project HEIST, which was launched by NATO in July last year, involves developing the means to sense cable breaks automatically, reroute internet from the cables to satellites and restore links rapidly. And at the moment, in the interim period after a cable break satellite internet can provide minimal connectivity to support essential operations.

Elon Musk’s Starlink provides coverage to around 70 countries and has often been brought in to help at short notice when disaster has struck – as it did in Tonga last year. In terms of the volume of the data sent from one place to another via subsea cable, current RF satellite internet can’t compare.

For that reason, it’s crucial to continue to invest in resilient emerging forms of technology. There is already extensive optical (laser) mesh net connectivity between satellites, which can move Gigbits of data around in space. The end point of using that data is high-speed connectivity to the ground – hence the need to augment the current RF ground stations with optical ground stations.

There are already about 200 cable breaks every year around the world. Last year, there were major undersea cable incidents in the Middle East, India, Japan and Tonga. There was suspected sabotage in the Red Sea and the Baltic Sea.

NATO expansion and rising tensions with Russia and others increase the risk of further sabotage. Given this, and given the centrality of internet connectivity to everyday life, as well as to national defense, developing solutions, and the technology involved in those solutions, is not a ‘good idea’ or a ‘nice-to-have’. It’s a matter of urgency.

Jeff Huggins is the president of Cailabs US Inc.